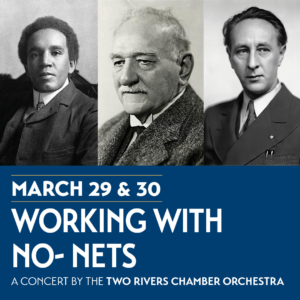

Working with NoNets – March 29 & 30, 2025

Introduction – Regarding Nonets

Introduction – Regarding Nonets

A musical nonet is a work scored for nine instrumentalists or singers. The form came into its own primarily in the early Romantic period, when relatively large chamber groups were becoming increasingly fashionable, especially in Vienna. This happened partly because putting together larger chamber groups was easier than gathering the dozens of musicians required for a full-sized orchestra. In addition, larger chamber groups created a richer sound than smaller ones.

Music for large wind bands or string ensembles used in outdoor entertainments predated nonets, but it was the Austrian composer Ludwig Spohr (1784–1859) who focused attention on the nonet form with his Nonet in F Major, Op. 31. This work, composed in 1813, was scored for flute, oboe, clarinet, horn, bassoon, violin, viola, cello, and double bass. Spohr’s compositional expertise and the fresh, new sonic palette his nonet displayed created an instant standard for this emerging genre, and many composers throughout Europe were inspired to create nonets of their own for many years to come.

Among those so inspired was the young British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875–1912), who wrote his own nonet (though with a slight change in instrumentation) in 1894 while still a student at the Royal Music College in London. This work, Coleridge-Taylor’s Nonet in F minor, Op. 2, is the first work you will hear in our concert.

Three decades later, in 1924, Spohr’s nonet inspired a group of nine musicians in Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic) to create their own musical group, called The Czech Nonet, that was originally devoted specifically to performing pieces of the genre.

The Czech Nonet is still going strong and over the years it has been responsible for the commission of many new nonets, including the other two works in our concert. One of these works, the Nonet, Op. 147 by the Czech composer Josef Foerster (1859–1951), was written in 1924 for the The Czech Nonet’s inaugural concert. The other work, the Nonet No. 2, H 374 by another Czech composer, Bohuslav Martinů (1890–1959), was written in 1959. It was one of the last pieces this great 20th century composer would write.

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

(Born in Holborn [London], England in 1875; died in Croydon [London], England in 1912)

Nonet in F minor, “Gradus ad Parnassum,” Op. 2

1. Allegro moderato — Tranquillo

2. Andante con moto — Più lento

3. Scherzo: Allegro — Trio — Scherzo da capo

4. Finale: Allegro vivace — Tranquillo — Più presto

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was an outstanding English composer and conductor, whose list of compositions is long and impressive for his short career. Of particular social importance at the time, too, was Coleridge-Taylor’s racial heritage. His father, Daniel Taylor, who was from Sierra Leone, studied medicine in London where he met Coleridge-Taylor’s mother, Alice Martin. Around the time Samuel was conceived, however, Daniel was forbidden from practicing medicine in England, and he had little choice but to return to Sierra Leone to practice there. Alice chose to stay in London with their son and named him in honor of England’s great poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, inverting the order of his surnames. Precociously talented in music, Samuel was enrolled in the Royal College of Music in London. His career soon began to blossom immensely, especially in America. But at age 37, just when his career and racial heritage were providing a beacon of hope for people of color in the Western world, he succumbed to pneumonia.

During his student years at the Royal College, the 18-year-old Coleridge-Taylor busily wrote music, creating three particularly fine chamber pieces: his Piano Quintet, Op. 1, a trio for strings and piano (not published in his lifetime), and his Nonet, Op. 2. Across the top of his nonet, the young composer wrote “Gradus ad Parnassum” (“A Step Toward Parnassus”) — likely a playful reference to Carl Czerny’s ubiquitous piano study book entitled Nouveau Gradus ad Parnassum (1854). Coleridge-Taylor’s nonet shows that the young Royal College student had already scaled Parnassus with his powers of melodic invention and the magnificent sound palette he created. He scored the work for oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn, violin, viola, cello, double bass, and piano (instead of Ludwig Spohr’s flute). The addition of the piano provided near-orchestral power and color.

The first theme of the first movement, Allegro moderato (moderately slow), showcases Coleridge-Taylor’s talents with melody. After one introductory bar, the clarinet sings one of Coleridge-Taylor’s most lyrical inventions, romantic and wistful. Underneath, the piano plays rich chords on the offbeats while the viola and cello create a quietly propulsive, skipping rhythm, giving the clarinet’s wistfulness a sense of insistence. When the clarinet finishes this first iteration, the theme opens up in sonic splendor as the rest of the nonet instruments, especially the piano, embellish on the theme. About a minute later, a second theme, bright and optimistic, is introduced first by the piano. These two themes and this skipping rhythm then populate the rest of the movement, but most lovely is Coleridge-Taylor’s inventiveness with different instrumental pairings, creating rich and exquisite hues.

The second movement, Andante con moto (slowly but with motion), begins with a short, dark introduction from the piano, played in octaves, and rumbling mysteriously in the low registers. Except for a brief reminder of this cautionary phrase at about four and a half minutes, the Andante unfurls with increasing beauty and inner joy. Notice how the skipping rhythm from the first movement dances effervescently throughout this movement as well.

The third movement, Scherzo, was singled out for praise when the Nonet had its premiere in 1894: “The scherzo is unquestionably the most striking movement, and few would guess it to be the work of one still a student,” one reviewer wrote. And indeed, this movement is a joyful ride of exuberance and great craft. The first section, Allegro, is simmering with gusto, capering between instrumental sections, featuring the winds, or pizzicato strings, or the piano, all skipping around each other excitedly. The middle section, Trio, starting at about two and a half minutes, follows this frolicking with tender rhapsodizing.

The last movement, Allegro vivace (fast and lively), is filled with joie de vivre. Coleridge-Taylor treats this finale as a nonstop tour de force of technical brilliance for all the instruments, with the pianist taking on an especially virtuosic role. The main theme, heard immediately, is youthfully strong, lyrical, and playful, and the lyricism never lets up. The ending section, Più presto (yet faster), begins with a pizzicato run by the viola, cello, and double bass, and then the entire nonet dashes to an invigorating end.

Josef Bohuslav Foerster

(Born in Prague, Czechoslovakia [now Czech Republic] in 1859; died in Nový Vestec, Czechoslovakia [now Czech Republic] in 1951)

Nonet: Variations on Two Themes, Op. 147

1. Allegro

2. Andante con moto

3. Andante con moto

4. Molto moderato

5. Allegro appassionato

6. Scherzoso e fantastico — Allegro ma non troppo

7. Andante con moto

8. Allegro moderato, ma molto appassionato

Josef Bohuslav Foerster was born in Prague, Czechoslovakia, to a family of artists. His grandfather, father, and paternal uncle were all respected composers, and his brother became a well-known muralist. The young Foerster studied music at the Prague Conservatory, finishing with a degree in composition, and then set out on a triple career as teacher, composer, and music critic. From 1893, Foerster made his living mainly as a critic and professor, first in Hamburg, Germany, then in Vienna, Austria, and eventually returning to teach at the Prague Conservatory in 1918. All the while, Foerster composed operas, symphonies, and dozens of chamber works.

In 1924, nine students of the Prague Conservatory founded the now famous (and still in existence) ensemble called The Czech Nonet. For their opening concert, they scheduled a performance of Spohr’s famous nonet for flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn, violin, viola, cello, and double bass, and also commissioned Foerster to write a new nonet for them, scored for the same instruments. Foerster happily obliged and the 1924 premiere in Vienna met with great praise. One critic gushed: “The atmosphere of Bohemia’s forests and meadows makes itself felt in this composition.… We are receiving the spirit of Dvořák from Foerster’s hands.”

Foerster’s nonet is indeed reminiscent of Dvorak’s gifts for pastoral lyricism, but it is deeply infused with Foerster’s own brand of more modern lyricism that incorporates a thoughtful dissonance, with notes that are allowed to fall out of the key as well as frequent key changes. Nonetheless, his nonet exudes a feeling of country calm and luster. Especially delightful is Foerster’s expert handling of the nine players: Each is treated with virtuosity and poeticism, and when all nine combine, they blaze with radiant colors.

The beginning movement, Allegro, presents the two themes that weave throughout the nonet. The first theme begins, cleverly, not with the theme itself but with an accompaniment in the winds that sounds rather comically as if they are waltzing with a limp. Then the bassoon enters to sing the first theme, which is at first galumphing but also lyrical and happy-go-lucky. The second theme appears less than a minute later, beginning with the oboe and then moving to the violin: It evokes a pastoral dreaminess, tinged with a hint of melancholy. The movement then expands on these two themes, ending quietly on plucked strings.

The second movement, Andante con moto (slow but with motion), begins with a solo viola and a variation that is filled with longing and vulnerability. After a pause, the opening viola strain repeats. Then, without any pause (attaca), the third movement, also marked Andante con moto, begins and becomes a graceful waltz with moments of brisk drama.

The fourth movement, Molto moderato (very moderately paced), starts with urgent, dramatic gestures and dissonance, but soon leads to a slower section, marked “dolcissimo, molto espressivo, ma tranquillo” (sweetly, very expressively, but tranquil), which features one of the nonet’s most lyrical violin solos. Again, without a pause (attaca), the fifth movement, Allegro appasionata (fast and with passion), begins. It opens with eight of the nine musicians playing a series of rapid-fire short notes in unison, moving into moments of fanciful rhapsodizing before it settles into its closing section of warmth and calm.

The sixth movement, Scherzoso e fantástico (playfully and fantastical), starts quietly with a hint of sinister intent but quickly turns into an engagingly insistent march that’s dappled with a certain songfulness. Different meters will appear throughout this movement — at one point, the four-beat march will be squeezed into three beats per measure. A surprise return of part of the second theme appears, and then the Scherzo ends with a few ebullient final bars.

The seventh movement, another Andante con moto, begins with a radiant clarinet solo singing languidly and peacefully. The pastoral second theme returns in full, and then the movement ends with the utmost vulnerability, marked to be played “dolente e patetico” (sorrowfully and movingly).

The final movement, Allegro moderato, ma molto appassionato (moderately fast and with much passion), begins with a surging energy but which soon pacifies. Following this initial surge and retreat, this movement becomes a recap of musical moments from the previous movements, with brief solos for everyone that then blend into longer full-ensemble passages. After a grand silence, the instruments race off with blistering speed, ending with great and joyous energy.

Bohuslav Jan Martinů

(Born in Polička, Czechoslovakia, [now Czech Republic] in 1890; died in Liestal, Switzerland in 1959)

Nonet No. 2, H 374

1. Poco allegro

2. Andante

3. Allegretto

Though never formally completing a music degree, the Czech composer Bohuslav Jan Martinů had an extraordinarily expansive approach to learning music, beginning with his lifelong love of Czech folk music. His musical explorations brought him to Paris in the early 1920’s where he discovered Igor Stravinsky’s neoclassicism (music adhering to structures and logic, that emulated the tenets of classicism and used sparser means than huge orchestral forces). This deeply informed his composing style for many years. But his musical genius was always devising new ways to express itself, and by the end of his life one could only truly define Martinů’s style as uniquely his own: Rhapsodic, often informed by his homeland’s folksongs and dance, clever, neoclassically inclined, rhythmically active, and always ingeniously inventive.

During World War II, Martinů took refuge in the United States. After the war, he yearned to return to his Czech home but the communist regime there made that goal unrealistic. By 1959 he was living in Switzerland and kept in close contact with his friends and colleagues in Prague. That year, The Czech Nonet commissioned Martinů for a new work for the ensemble’s 35th anniversary concert. He chose to write for them his Nonet No. 2 (also scored for flute, clarinet, oboe, bassoon, horn, violin, viola, cello, and double bass, like Foerster’s nonet). It would turn out to be one of his last completed compositions: He had been battling stomach cancer and died one month after the concert. Despite Martinů’s health challenges, his Nonet No. 2 is one of his most joyful works. It is often filled with the feeling of Czech folksong and dance, and with a kaleidoscope of colors and effervescent jubilance.

The first movement, Poco allegro (rather fast), is a festival of 10 separate themes, all packed into a short five minutes of music. The opening immediately portrays a sense of dance and glee as the clarinet begins a short little up-and-down-motive. This motive is then echoed in the strings at a faster pace, and within seconds, the entire nonet is burbling with excited iterations of the motive as solos from every instrument pop into the fabric with brief intensity. All of this excited tumbling culminates in a wonderfully regal horn solo at about two minutes. The movement then returns to and reworks the opening music and ends with happy bravura.

The second movement, Andante (at a walking pace), is a moment of stunning invention and noble beauty — perhaps one of the loveliest things that Martinů created. It begins with a cello solo in which the upper strings add quiet atmospheric zephyrs. Shortly, the strings branch into polyphonic wanderings (every instrument plays its own melody) that coalesce harmonically. It’s Martinů’s bewitching night music, filled with the sounds of every mysterious and beautiful thing at midnight. Particularly lovely is a passage, at about three and a half minutes, in which the flute and clarinet play together quietly and lyrically, and then the music becomes increasingly rhapsodic as more instruments join in. The bassoon, at last, brings this rhapsodic night music to rest, settling lower and lower into a soft chord with the full ensemble.

The final movement, Allegretto (not very fast), begins with bouncy and unpredictably happy chaos. The meter changes frequently, moving in and out of five beats per bar, and yet Martinů somehow balances all this restlessness with a sense of folkdance and jolliness. At about two minutes, the music calms and the flute and then the oboe, introduce a hymn-like tune. From here until the end, the feelings of folkdance and hymn take turns, each demanding ever more virtuosity from the players, until at last, the hymn-like tune closes the work with the horn heralding the ending bars with warm majesty.

© Max Derrickson